Background: Anatomy of a Hoof

Written By: Lauren Alderman, DVM, CVA, CVSMT

From Okanagan School of Natural Hoof Care

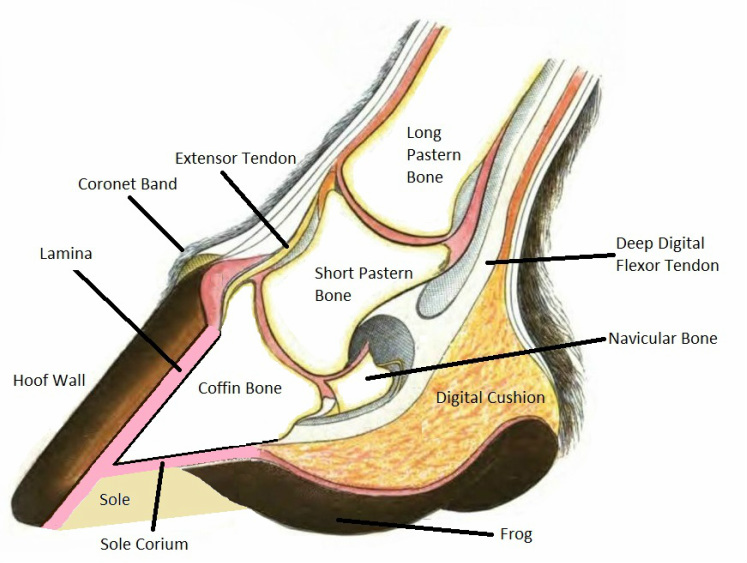

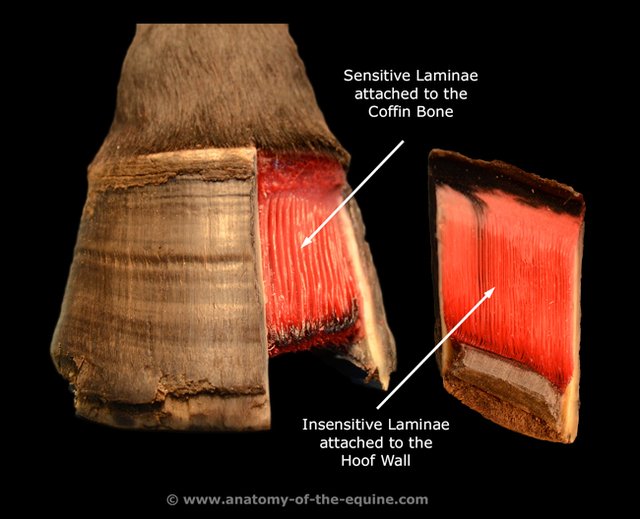

Equines bear weight on their coffin bone (aka. third phalanx/P3/pedal bone/distal phalanx). The coffin bone sits within the hoof capsule and is covered in a soft tissue structure called the corium, which is somewhat equivalent to the “quick” of your fingernail. The corium is responsible for providing nutrition to the hoof. The outermost layer of the corium forms microscopic finger-like projections called the dermal lamellae (often referred to as sensitive lamellae due to their vascular nature and nerve supply).

In a normal hoof, growth of the hoof wall occurs distally (from the coronet band toward the ground) from coronary corium, which is located in the region of the coronary (or coronet) band at the top of the hoof wall. This typically occurs at about 8-10mm per month. The innermost layer of the coronary corium also forms microscopic finger-like projections, called epidermal lamellae (often referred to as insensitive lamellae).

The coffin bone is anchored to the inside of the hoof wall by the interlocking nature of the dermal and epidermal lamellae. A horse’s weight is essentially suspended from the inner hoof wall by this very strong, live, velcro-like attachment. An extension of this region of attachment can be seen on the ground surface of the hoof, and is commonly referred to as the white line.

www.anatomy-of-the-equine.com

What is laminitis?

Laminitis can be defined as inflammation of the laminae that anchor the coffin bone within the hoof capsule.

Another term that may be encountered in discussions about laminitis is founder, which refers to the rotational and downward movement of the coffin bone within the hoof capsule. This sometimes occurs in severe cases of laminitis due to the breakdown of these crucial laminar attachments.

Signs of laminitis

A characteristic stance in a horse with acute laminitis. Photo from Horse and Hound.

A horse with acute laminitis will have hooves that appear clinically normal - the inflammation is not visible from the exterior of the hoof. Horses may present with anything from a mild lameness to a near refusal to bear weight. Depending on the severity of pain, a horse with acute laminitis may even lie down and refuse to stand. Lameness is often more severe when turning or walking on hard surfaces, and horses tend to adopt a characteristic stance in an effort to take weight off their toes - forelimbs extended and hind limbs tucked forward under the belly. These horses often resist lifting a foot because they are reluctant to place more weight on another foot. They frequently have bounding digital pulses that can be felt on the back of the pastern or fetlock and their hooves may feel hot to the touch. During an acute episode of laminitis, painful horses may be distressed, sweating, hyperventilating, and have an elevated heart rate.

A horse with acute founder will also have clinically normal hooves, with a sudden sinking of the coffin bone within the hoof capsule. If severe enough, this can ultimately progress to a catastrophic sloughing of the hoof.

Horses living with chronic laminitis will always be at risk of an acute-on-chronic episode, where laminar inflammation recurs. Severe acute-on-chronic episodes frequently lead to subsolar abscessation (hoof abscesses under the sole), and can possibly result in penetration of the sole by the tip of the coffin bone.

Horses with chronic stable laminitis may have experienced rotation and sinking of the coffin bone, but the coffin bone has since stabilized within the hoof capsule. Chronic laminitic changes in hoof conformation and blood supply often result in characteristic hoof growth patterns - a dished/concave dorsal hoof wall, laminitic growth rings (wider apart near the heel, closer together over the front of the hoof), and stretching of the white line. These horses are often predisposed to “white line disease” (sometimes called ”seedy toe”) and to the development of hoof abscesses.

Diagnosis of laminitis

A veterinarian will diagnose laminitis based on a horse’s clinical signs, history, and a thorough physical exam. A veterinarian will have a high suspicion of laminitis in a horse with a consistent positive (painful) response to hoof testers over the toe, especially if this is present in multiple hooves. Radiographs are a very valuable tool in evaluating these patients. Veterinarians look for new separation/rotation of the coffin bone compared to the dorsal hoof wall in acute cases, or for bony changes in the coffin bone that can indicate a chronic history of laminitis. Radiographs also provide important information when a veterinarian is making recommendations for shoeing changes and monitoring the efficacy of these changes.

Causes of laminitis

Obesity is a significant and important risk factor for developing laminitis. In addition, carbohydrate overload can cause a horse to develop laminitis. This can occur when a horse consumes lush pasture with a high sugar content, or when a horse is fed (or breaks into the feed room and gains unlimited access to) excess grain. Endotoxemia, or the presence of bacterial toxins within the bloodstream, can also lead to laminitis. Endotoxemia may occur with gastrointestinal disease such as Potomac Horse Fever, pneumonia or pleuritis, retained placenta or metritis, or any other significant systemic infection.

“Road founder” is a term referring to a type of laminitis that may be seen when sudden hoof stress occurs (such as a horse running for an extended period of time on a hard surface or an inexperienced person trimming hooves too short).

A horse may also develop supporting limb laminitis (laminitis in a “good leg”) when severe lameness is present in one limb or when a fracture has been repaired. As many people in the horse world are aware, this was the tragic fate of the racehorse Barbaro who fractured his leg during a race and later developed laminitis in his other legs.

Black walnut wood shavings contain a toxin that will cause horses to develop laminitis if they are bedded on the material.

Corticosteroids, which are commonly used to control inflammation (for example, in joint injections or in the treatment of allergies), also carry a small risk of causing laminitis. For this reason, veterinarians are very careful to prescribe and use the lowest possible doses of steroids. Unfortunately, some individual horses seem to be more sensitive to developing adverse effects with corticosteroid use, and it is difficult to predict which horses will be more sensitive.

Horses with PPID (Cushing’s Syndrome) are also at a higher risk of eventually developing laminitis. In fact, a veterinarian may suggest testing a horse for PPID if laminitis signs develop for no other apparent reason.

Management of laminitis

A horse with acute laminitis is in need of immediate pain management. A veterinarian will recommend strict stall rest with deep shavings or sand, and may recommend cold hosing or icing the horse’s feet. Anti-inflammatories such as bute or banamine will typically be used. Some veterinarians may also administer aspirin or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). In addition, a veterinarian may used medications such as acepromazine or pentoxifylline in an effort to modify blood flow in the hooves. In addition to supporting the hooves with deep bedding, a veterinarian may also often recommend using styrofoam padding or Soft Ride Boots to help keep the horse more comfortable.

For horses living with chronic laminitis, management is crucial. Keeping a laminitic horse at a healthy weight is incredibly important in order to minimize the stress placed on the sensitive structures in the hoof. Grain and concentrate feeds should be avoided if at all possible to minimize carbohydrate intake - these horses may be supplemented with fat if weight gain is necessary. Caution should be taken when considering allowing a laminitic horse access to pasture, especially during high risk times such as spring and late summer when grass tends to have a higher sugar content. Unfortunately it is very difficult to predict pasture sugar levels at any given time, so veterinarians will often recommend turning horses out with a grazing muzzle or keeping them off grass altogether. Horses kept on a dry lot can be fed hay in a slow feeder hay net to keep them occupied and control their intake. Some horses that are especially sensitive to sugar in their feed may benefit from being fed hay that has been tested and determined to be lower in sugar.

Horses with chronic laminitis may require intermittent administration of anti-inflammatories such as bute or Equioxx to help them stay comfortable during flare-ups.

In a horse with stable chronic laminitis, shoeing changes should also be implemented in an effort to restore the parallel alignment between the coffin bone and the dorsal hoof wall. A veterinarian and farrier will discuss providing heel and frog support, using pads or pour-ins, and easing the breakover of the toe to reduce stresses on the laminae and minimize stretching of the white line.

Prognosis

Unfortunately, laminitis is an unpredictable condition that can be very frustrating to treat and manage. It can be very difficult for veterinarians to provide a definitive prognosis, as the progression of laminitis varies greatly between individual patients. A patient will have a better prognosis if they respond quickly to treatment and if treatment is implemented before significant laminar damage has occurred. A poorer prognosis is likely for a horse that does not respond quickly to treatment or if the coffin bone has rotated. When rotation and sinking of the coffin bone occurs, prognosis is often grave.

Prevention

Careful monitoring and management of any horse with the previously mentioned causes of laminitis is an essential component of prevention. It is important to be proactive and keep your veterinarian updated on the condition of these patients.

For example, broodmares with metritis or a retained placenta (placenta not passed within several hours of foaling) are at risk for developing laminitis. Another unfortunate scenario is a horse that breaks into the feed room and has unrestricted access to grain. These horses should receive emergency treatment before the onset of clinical signs of laminitis or gastrointestinal distress.

Questions? Contact us.